“Brazil was the last country in the Western world to abolish slavery, on May 13, 1888, and Portugal was one of the first European empires to make slavery the primary tool of its colonization of the Atlantic world. The colonists who landed in Brazil in 1530 to establish sugar cane plantations and mills to process the cane—an enterprise that had been proved successful on the island of Madeira—quickly turned to servile labor to clear and cultivate the land. The first contingents of slaves were drawn from the native populations, but this course rapidly revealed itself to be impractical. The epidemic diseases brought from Europe decimated the indigenous populations even more quickly when Indians were concentrated together to labor. And the Jesuit missionaries who arrived alongside the first colonists had other projects in mind for the indigenous peoples: They believed that conversion depended on a rejection of native culture, and that the latter would result once the Indians had become wage-earning rural workers rather than slaves. The Tupi themselves did not take to agricultural work, which they considered subsistence labor proper only for women.[5] (…) So when the Portuguese crown, trying to satisfy the Company of Jesus, placed strict regulations on the enslavement of Indians in Brazil, colonists looked to the transfer of African captives from the other side of the Atlantic (….) The comfortable profits being produced by the plantations further stimulated the transition. By 1570, the first slave ships had arrived in Brazil, and they did not stop arriving until 1850, when the trans-Atlantic transfer of captives to Brazil was finally effectively outlawed. Between these two dates, four to five million Africans were shipped overseas to work and live as slaves in the plantations, mines, and cities of Brazil.”

Read more

Until the early 1850s, most enslaved Africans who arrived on Brazilian shores were forced to embark at West Central African ports, especially in Luanda (present-day Angola).

Alberto Henschel

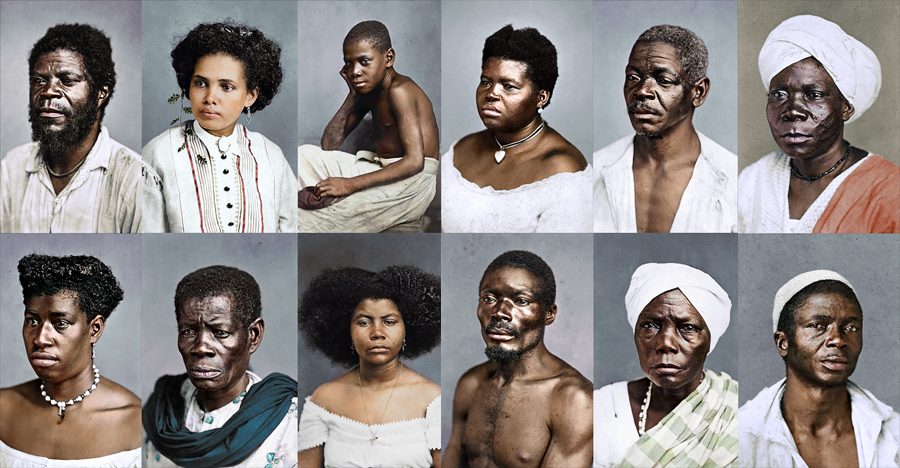

Alberto Henschel was a German-Brazilian photographer born in Berlin. Considered the hardest-working photographer and businessman in 19th-century Brazil, with offices in Pernambuco, Bahia, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo, Henschel was also responsible for the presence of other professional photographers in the country, including his compatriot Karl Ernst Papf—with whom he later worked. Henschel became known for making pictorial representations of Rio de Janeiro as a landscaper photographer and for being an excellent portraitist. He earned the title of “Fotógrafo da Casa Imperial”, which allowed him to photograph the everyday life of the Brazilian monarchy during the Reign of Pedro II. This title would give his photographs increased recognition and raise their price.

Henschel’s most important contribution to the history of photography in Brazil is the portraits he took of people of African origin, slaves and free, “differing him from other photographers because he tried to portray them freely and with dignity, as people and not as objects”.

You can now see some of the photos in color for the first time.

[twenty20 img1=”6173″ img2=”6172″ offset=”0.5″]

[twenty20 img1=”6176″ img2=”6175″ offset=”0.5″]

[twenty20 img1=”6179″ img2=”6178″ offset=”0.5″]

[twenty20 img1=”6181″ img2=”6180″ offset=”0.5″]

[twenty20 img1=”6184″ img2=”6183″ offset=”0.5″]

[twenty20 img1=”6186″ img2=”6185″ offset=”0.5″]

[twenty20 img1=”6188″ img2=”6187″ offset=”0.5″]

[twenty20 img1=”6190″ img2=”6189″ offset=”0.5″]

[twenty20 img1=”6192″ img2=”6191″ offset=”0.5″]

[twenty20 img1=”6194″ img2=”6193″ offset=”0.5″]

[twenty20 img1=”6196″ img2=”6195″ offset=”0.5″]

[twenty20 img1=”6198″ img2=”6203″ offset=”0.5″]

[twenty20 img1=”6201″ img2=”6199″ offset=”0.5″]

About this project

The art of colorizing has been around since the 1840s. Watercolors, oils, crayons and pastels, among others, were applied to the photos in an attempt to create more realistic images. This is not an attempt to replace the original photographs, which are highly important and of extreme historical value, but, as in my other works, it is an attempt to humanize the people portrayed. It is also an attempt to individualize them, and show that they are not only characters in history books.

As nothing is known about the men and women in the photos, I could not do much research. Therefore, the colors you see here are an artistic interpretation, based on my experience, observation, modern photographs, basic preliminary research and artistic guesses. For this reason, they are not necessarily 100% accurate but are as close as possible given the limitations I had throughout the process. The original photographs can be found at the Leibniz-Institut Für Länderkunde, Instituto Moreira Sales (Brazil), Ethnologisches Museum der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, and other archives. The photographs were taken in Recife and Salvador, circa 1869. Henschel’s biography was extracted from Wikipedia.

The photos were produced in the carte-de-visite format, which makes the colorization process a bit more complicated. Bright areas often lose detail and texture (hence why specific areas look too bright, in the original and in the colorized version), which makes the skin “shine” after the contrast is corrected. It is very hard to adjust this without ruining the photograph, so this aspect is maintained in the colorized version.

The carte de visite was usually made of an albumen print, which was a thin paper photograph mounted on a thicker paper card.

Download (Free use for educational purposes. Commercial use not allowed. For reproduction, please reach out first.)

Resources for the study of slavery and abolition in Latin America.